The Taman Shud Case, also known as the Mystery of the Somerton Man, is an unsolved case of an unidentified man found dead at 6:30 a.m., 1 December 1948, on Somerton beach in Adelaide, South Australia. It is named after a phrase, tamam shud, meaning “ended” or “finished” in Persian, on a scrap of the final page of The Rubaiyat, found in the hidden pocket of the man’s trousers.

Considered “one of Australia’s most profound mysteries” at the time, the case has been the subject of intense speculation over the years regarding the identity of the victim, the events leading up to his death, and the cause of death. Public interest in the case remains significant because of a number of factors: the death occurring at a time of heightened tensions during the Cold War, what appeared to be a secret code on a scrap of paper found in his pocket, the use of an undetectable poison, his lack of identification, and the possibility of unrequited love.

While the case has received the most scrutiny in Australia, it also gained international coverage, as the police widely distributed materials in an effort to identify the body, and consulted with other governments in tracking down leads.

Victim

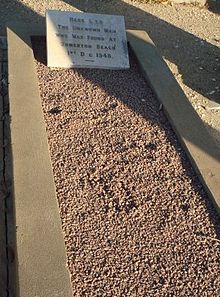

The body was discovered at 6:30 a.m. on 1 December 1948 on Somerton beach in Adelaide, South Australia, and the police were called. When they arrived, the body was lying on the sand with its head resting on the seawall, and with its feet crossed and pointing directly to the sea. The police noted no disturbance to the body and observed that the man’s left arm was in a straight position and the right arm was bent double. An unlit cigarette was behind his ear and a half-smoked cigarette was on the right collar of his coat held in position by his cheek. A search of his pockets revealed an unused second-class rail ticket from the city to Henley Beach, a used bus ticket from the city, a narrow aluminum American comb, a half-empty packet of Juicy Fruit chewing gum, an Army Club cigarette packet containing Kensitas cigarettes, and a quarter-full box of Bryant & May matches. The bus stop for which the ticket was used was around 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) north of the body’s location. The man had no money in his pockets.

Witnesses who came forward said that on the evening of 30 November, they had seen an individual resembling the dead man lying on his back in the same spot and position near the Crippled Children’s Home where the corpse was later found. A couple who saw him around 7 p.m. noted that they saw him extend his right arm to its fullest extent and then drop it limply. Another couple who saw him from 7:30 p.m. to 8 p.m., during which time the street lights had come on, recounted that they did not see him move during the half an hour in which he was in view, although they did have the impression that his position had changed. Although they commented between themselves that he must be dead because he was not reacting to the mosquitoes, they had thought it more likely that he was drunk or asleep, and thus did not investigate further. Witnesses said the body was in the same position when the police viewed it.

According to the pathologist, Sir John Burton Cleland, emeritus professor at the University of Adelaide, the man was of “Britisher” appearance and thought to be aged about 40–45; he was in top physical condition. He was 180 centimeters (5 ft 11 in) tall, with hazel eyes, fair to ginger-coloured hair, slightly grey around the temples, with broad shoulders and a narrow waist, hands and nails that showed no signs of manual labour, big and little toes that met in a wedge shape, like those of a dancer or someone who wore boots with pointed toes; and pronounced high calf muscles like those of a ballet dancer. These can be dominant genetic traits, and they are also a characteristic of many middle and long-distance runners. He was dressed in “quality clothing”: consisting of a white shirt, red and blue tie, brown trousers, socks and shoes and, although it had been a hot day and very warm night, a brown knitted pullover and fashionable European grey and brown double-breasted coat. All labels on his clothes were missing, and he had no hat (unusual for 1948, and especially so for someone wearing a suit) or wallet. Clean-shaven and with no distinguishing marks, the man carried no identification, which led police to believe he had committed suicide. His teeth did not match the dental records of any known person in Australia.

Autopsy

An autopsy was conducted, and the pathologist estimated the time of death at around 2 a.m. on 1 December.

“The heart was of normal size, and normal in every way …small vessels not commonly observed in the brain were easily discernible with congestion. There was congestion of the pharynx, and the gullet was covered with whitening of superficial layers of the mucosa with a patch of ulceration in the middle of it. The stomach was deeply congested…There was congestion in the 2nd half of the duodenum. There was blood mixed with the food in the stomach. Both kidneys were congested, and the liver contained a great excess of blood in its vessels. …The spleen was strikingly large … about 3 times normal size … there was destruction of the centre of the liver lobules revealed under the microscope. … acute gastritis hemorrhage, extensive congestion of the liver and spleen, and the congestion to the brain.”

The autopsy showed that the man’s last meal was a pasty eaten three to four hours before death,[5] but tests failed to reveal any foreign substance in the body. The pathologist Dr. Dwyer concluded: “I am quite convinced the death could not have been natural …the poison I suggested was a barbiturate or a soluble hypnotic”. Although poisoning remained a prime suspicion, the pasty was not believed to be the source of the poison.[8] Other than that, the coroner was unable to reach a conclusion as to the man’s identity, cause of death, or whether the man seen alive at Somerton Beach on the evening of 30 November was the same man, as nobody had seen his face at that time.[13] Scotland Yard was called in to assist with the case but with little result.[16] Wide circulation in the world of a photograph of the man and details of his fingerprints yielded no positive identification.[8]

As the body was not identified, it was embalmed on 10 December 1948. The police said this was the first time they knew that such action was needed.[17]

Media reaction

The two daily Adelaide newspapers, The Advertiser and The News, covered the death in separate ways. The Advertiser, then a morning broadsheet, first mentioned the case in a small article on page three of its 2 December 1948 edition. Entitled “Body found on Beach”, it read:

“A body, believed to be of E.C. Johnson, about 45, of Arthur St, Payneham, was found on Somerton Beach, opposite the Crippled Children’s Home yesterday morning. The discovery was made by Mr J. Lyons, of Whyte Rd, Somerton. Detective H. Strangway and Constable J. Moss are enquiring.”[18]

The News, an afternoon tabloid, featured their story of the man on its first page, giving more details of the dead man.[4]

Identification

On 3 December 1948, E.C. Johnson walked into a police station to identify himself as living and was dropped from potential as the dead man.[7][19] That same day, The News published a photograph of the dead man on its front page,[20] leading to additional calls from members of the public about the possible identity of the dead man. By the fourth of December, police had announced that the man’s fingerprints were not on South Australian police records, forcing them to look further afield.[21] On 5 December, The Advertiser reported that police were searching through military records after a man claimed to have had a drink with a man resembling the dead man at a hotel in Glenelgon 13 November. During their drinking session, the mystery man supposedly produced a military pension card bearing the name “Solomonson”.[22]

A number of possible identifications of the body were made, including one in early January 1949 when two people identified the body as that of 63-year-old former wood cutter Robert Walsh.[23] A third person, James Mack, also viewed the body, initially could not identify it, but an hour later he contacted police to claim it was Robert Walsh. Mack stated that the reason he did not confirm this at the viewing was a difference in the colour of the hair. Walsh had left Adelaide several months earlier to buy sheep in Queensland but had failed to return at Christmas as planned.[24] Police were sceptical, believing Walsh to be too old to be the dead man. However, the police did state that the body was consistent with that of a man who had been a wood cutter, although the state of the man’s hands indicated he had not cut wood for at least 18 months.[25] Any thoughts that a positive identification had been made were quashed, however, when Mrs Elizabeth Thompson, one of the people who had earlier positively identified the body as Mr Walsh, retracted her statement after a second viewing of the body, where the absence of a particular scar on the body, as well as the size of the dead man’s legs, led her to realise the body was not Mr Walsh.[26]

By early February 1949, there had been eight different “positive” identifications of the body,[27] including two Darwin men who thought the body was of a friend of theirs,[28] and others who thought it was a missing stablehand, a worker on a steamship[29] or a Swedish man.[27] Victorian detectives initially believed the man was from the state of Victoria because of the similarity of the laundry marks to those used by several dry-cleaning firms in Melbourne.[30]Following publication of the man’s photograph in Victoria, 28 people claimed they knew his identity. Victorian detectives disproved all the claims and said that “other investigations” indicated it was unlikely that he was a Victorian.[31]

By November 1953, police announced they had recently received the 251st “solution” to the identity of the body from members of the public who claimed to have met or known him. But, they said that the “only clue of any value” remained the clothing the man wore.[32]

Brown suitcase

Also in the suitcase was a thread card of Barbour brand orange waxed thread of “an unusual type” not available in Australia—it was the same as that used to repair the lining in a pocket of the trousers the dead man was wearing.[34] All identification marks on the clothes had been removed but police found the name “T. Keane” on a tie, “Keane” on a laundry bag and “Kean” (without the last e) on a singlet, along with three dry-cleaning marks; 1171/7, 4393/7 and 3053/7.[35][36] Police believed that whoever removed the clothing tags purposefully left the Keane tags on the clothes, knowing Keane was not the dead man’s name.[34] It has since been noted that the “Kean” tags were the only ones that could not have been removed without damaging the clothing.

Another seaman, Tommy Reade from the SS Cycle, in port at the time, was thought to be the dead man but after some of his shipmates viewed the body at the morgue, they stated categorically that the corpse was not that of Tommy Reade.[37] A search concluded that there was no T. Keane missing in any English-speaking country[38] and a nation-wide circulation of the dry-cleaning marks also proved fruitless. In fact, all that could be garnered from the suitcase was that since a coat in the suitcase had a front gusset and featherstitching, it could have been made only in the United States, as this was the only country that possessed the machinery for that stitch. Although mass-produced, the body work is done when the owner is fitted before it is completed. The coat had not been imported, indicating the man had been in the United States or bought the coat from someone of similar size who had been.[12][39]

Police checked incoming train records and believed the man had arrived by overnight train from either Melbourne,[40] Sydney or Port Augusta.[8] They believed he then showered and shaved at the adjacent City Baths before returning to the train station to purchase a ticket for the 10:50 a.m. train to Henley Beach, which, for whatever reason, he missed or did not catch.[34] After returning from the city baths, he checked in his suitcase at the station cloak room before catching a bus to Glenelg.[41] Derek Abbott, who studied the case, believes that the man may have purchased the train ticket before showering. The railway station’s own public facilities were closed that day and discovering this and then having to walk to the adjacent city baths to shower would have added up to 30 minutes to the time he would have expected to take, which could explain why he missed the Henley Beach train and took the next available bus.

Inquest

A coroner’s inquest into the death, conducted by coroner Thomas Erskine Cleland, commenced a few days after the body was found but was adjourned until 17 June 1949. The investigating pathologist Sir John Burton Cleland re-

Thomas Cleland speculated that as none of the witnesses could positively identify the man they saw the previous night as being the same person discovered the next morning, there remained the possibility the man had died elsewhere and had been dumped. He stressed that this was purely speculation as all the witnesses believed it was “definitely the same person” as the body was in the same place and lying in the same distinctive position. He also found there was no evidence as to who the deceased was.

Cedric Stanton Hicks, Professor of Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Adelaide, testified that of a group of drugs, variants of a drug in that group he called number 1 and in particular number 2 were extremely toxic in a relatively small oral dose that would be extremely difficult if not impossible to identify even if it had been suspected in the first instance. He gave the coroner a piece of paper with the names of the two drugs which was entered as Exhibit C.18. The names were not released to the public until the 1980s as at the time they were “quite easily procurable by the ordinary individual” from a chemist without the need to give a reason for the purchase. (The drugs were later publicly identified as digitalis and ouabain.) He noted the only “fact” not found in relation to the body was evidence of vomiting. He then stated its absence was not unknown but that he could not make a “frank conclusion” without it. Hicks stated that if death had occurred seven hours after the man was last seen to move, it would imply a massive dose that could still have been undetectable. It was noted that the movement seen by witnesses at 7 p.m. could have been the last convulsion preceding death.

Early in the inquiry, Cleland stated “I would be prepared to find that he died from poison, that the poison was probably a glucoside and that it was not accidentally administered; but I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person.” Despite these findings, he could not determine the cause of death of the Somerton Man.

The lack of success in determining the identity and cause of death of the Somerton Man had led authorities to call it an “unparalleled mystery” and believe that the cause of death might never be known.

An editorial called the case “one of Australia’s most profound mysteries” and noted that if he died by poison so rare and obscure it could not be identified by toxicology experts, then surely the culprit’s advanced knowledge of toxic substances pointed to something more serious than a mere domestic poisoning..

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Around the same time as the inquest, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words “Tamam Shud” printed on it was found deep in a fob pocket sewn within the dead man’s trouser pocket. Public library officials called in to translate the text identified it as a phrase meaning “ended” or “finished” found on the last page of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The paper’s verso side was blank. Police conducted an Australia-wide search to find a copy of the book that had a similarly blank verso. A photograph of the scrap of paper was sent to interstate police and released to the public, leading a man to reveal he had found a very rare first edition copy of Edward FitzGerald’s 1859 translation of The Rubaiyat, published by Whitcombe and Tombs in New Zealand, in the back seat of his unlocked car that had been parked in Jetty Road Glenelg about a week or two before the body was found. He had known nothing of the book’s connection to the case until he saw an article in the previous day’s newspaper. This man’s identity and profession were withheld by the police, as he wished to remain anonymous.

The theme of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is that one should live life to the full and have no regrets when it ends. The poem’s subject led police to theorise that the man had committed suicide by poison, although there was no other evidence to back the theory. The book was missing the words “Tamam Shud” on the last page, which had a blank reverse, and microscopic tests indicated that the piece of paper was from the page torn from the book.

- WRGOABABD

MLIAOI- WTBIMPANETP

- MLIABOAIAQC

- ITTMTSAMSTGAB[40]

In the book it is unclear if the first two lines begin with an “M” or “W”, but they are widely believed to be the letter W, owing to the distinctive difference when compared to the stricken letter M. There appears to be a deleted or underlined line of text that reads “MLIAOI”. Although the last character in this line of text looks like an “L”, it is fairly clear on closer inspection of the image that this is formed from an ‘I’ and the extension of the line used to delete or underline that line of text. Also, the other “L” has a curve to the bottom part of the character. There is also an “X” above the last ‘O’ in the code, and it is not known if this is significant to the code or not. Initially, the letters were thought to be words in a foreign language before it was realized it was a code. Code experts were called in at the time to decipher the lines but were unsuccessful. When the code was analyzed by the Australian Department of Defence in 1978, they made the following statements about the code:

- There are insufficient symbols to provide a pattern.

- The symbols could be a complex substitute code or the meaningless response to a disturbed mind.

- It is not possible to provide a satisfactory answer.

Also found in the back of the book was an unlisted telephone number belonging to a former nurse who lived in Moseley St, Glenelg, around 400 metres (1,300 ft) north of the location where the body was found. The woman said that while she was working at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney during World War II she owned a copy of The Rubaiyat but in 1945, at the Clifton Gardens Hotel in Sydney, had given it to an army lieutenant named Alfred Boxall who was serving in the Water Transport Section of the Australian Army.

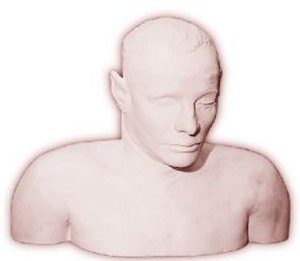

According to media reports the woman stated that after the war she had moved to Melbourne and married. Later she had received a letter from Boxall, but had told him she was now married. She added that in late 1948 a mystery man had asked her next door neighbour about her. There is no evidence that Boxall, who did not know the woman’s married name, had any contact with her after 1945. Shown the plaster cast bust of the dead man by Detective sergeant Leane, the woman could not identify it. According to Leane, he described her reaction upon seeing the cast as “completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance that she was about to faint.” In his 2002 video interview, Paul Lawson, the technician who made the body cast and was present when the woman viewed it, refers to her as ‘Mrs Thomson’ and noted that after looking at the bust she immediately looked away and would not look at it again.

Police believed that Boxall was the dead man until they found Boxall alive with his copy of The Rubaiyat (a 1924 Sydney edition), complete with “Tamam Shud” on the last page. Boxall was now working in the maintenance section at the Randwick Bus Depot (where he had worked before the war) and was unaware of any link between the dead man and himself. In the front of the copy of the Rubaiyat that was given to Boxall, the woman had written out verse 70:

- Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft before

- I swore—but was I sober when I swore?

- And then and then came Spring, and Rose-in-hand

- My thread-bare Penitence a-pieces tore.

The woman now lived in Glenelg but denied all knowledge of the dead man or why he would choose to visit her suburb on the night of his death. She also asked that as she was now married she would prefer not to have her name recorded to save her from potential embarrassment of being linked to the dead man and Boxall. The police agreed, leaving subsequent investigations without the benefit of the case’s best lead. In a TV programme on the case, in the section where Boxall was interviewed, her name was given in a voice-over as Jestyn, apparently obtained from the signature Jestyn that followed the verse written in the front of the book, but this was covered over when the book was displayed in the programme. This was possibly a “pet” nickname and was the name she used when introduced to Boxall. Retired detective Gerald Feltus, who had handled the cold case, interviewed Jestyn in 2002 and found her to be either “evasive” or “just did not wish to talk about it,” she also stated that her family did not know of her connection with the case and he agreed not to disclose her identity or anything that might reveal it. Feltus believes that Jestyn knew the Somerton man’s identity. Jestyn had told police that she was married, but they did not record Jestyn’s name on the police file, and there is no evidence that police at the time knew that she was in fact not married. Researchers re-investigating the case attempted to track down Jestyn and found she had died in 2007. Her real name was considered important as the possibility exists that it may be the decryption key for the code. In his 2010 book, Feltus claims he was given permission by Jestyn’s husband’s family to disclose the names; however, the names he revealed in his book are believed to be pseudonyms.

Spy theory

Rumours began circulating that Boxall was involved in military intelligence during the War, adding to the speculation that the dead man was a Soviet spy poisoned by unknown enemies. In a 1978 television interview with Boxall, the interviewer states, “Mr Boxall, you had been working, hadn’t you, in an intelligence unit, before you met this young woman [Jestyn]. Did you talk to her about that at all?” In reply he stated “No,” and when asked if she could have known, Boxall replied “not unless somebody else told her.” When the interviewer went on to suggest that there was a spy connection, Boxall replied after a pause, “It’s quite a melodramatic thesis, isn’t it?” In fact Alfred Boxall was an engineer in the 4th Water Transport Company seconded to the 2/1st North Australia Observer Unit (NAOU) for special operations under the direct command of the GOC. During secondment, he rose in rank from Lance corporal to Lieutenant in three months.

The fact that the man died in Adelaide, the nearest capital city to Woomera, a top-secret missile launching and intelligence gathering site, heightened this speculation. It was also recalled that one possible location from which the man might have travelled to Adelaide was Port Augusta, a town relatively close to Woomera.

Additionally, in April 1947 the United States Army’s Signal Intelligence Service, as part of Operation Venona, discovered that there had been top secret material leaked from Australia’s Department of External Affairs to the Soviet embassy in Canberra. This led to a 1948 U.S. ban on the transfer of all classified information to Australia.

As a response, the Australian government announced that it would establish a national secret security service (which became the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO)).[65]

Post-inquest

Years after the burial, flowers began appearing on the grave. Police questioned a woman seen leaving the cemetery but she claimed she knew nothing of the man.[13] About the same time, the receptionist from the Strathmore Hotel, opposite Adelaide Railway Station, revealed that a strange man had stayed in Room 21 around the time of the death, checking out on 30 November 1948. She recalled that cleaners found a black medical case and a hypodermic syringe in the room.[13]

On 22 November 1959 it was reported that an E.B. Collins, an inmate of New Zealand’s Wanganui Prison, claimed to know the identity of the dead man.[12]

There have been numerous unsuccessful attempts in the 60 years since its discovery to crack the letters found at the rear of the book, including efforts by military and naval intelligence, mathematicians, astrologers and amateur code crackers.[67] In 2004, retired detective Gerry Feltus suggested in a Sunday Mail article that the final line “ITTMTSAMSTGAB” could stand for the initials of “It’s Time To Move To South Australia Moseley Street…” (the former nurse lived in Moseley Street which is the main road through Glenelg).[8] A 2014 analysis by computational linguist John Rehling strongly supports the theory that the letters consist of the initials of some English text, but finds no match for these in a large survey of literature, and concludes that the letters were likely written as a form of shorthand, not as a code, and that the original text can likely never be determined. [68]

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation, in its documentary series Inside Story, in 1978 produced a programme on the Tamam Shud case, entitled The Somerton Beach Mystery, where reporter Stuart Littlemore investigated the case, including interviewing Boxall, who could add no new information on the case,[54] and Paul Lawson, who made the plaster cast of the body, and who refused to answer a question about whether anyone had positively identified the body.[50]

In 1994 John Harber Phillips, Chief Justice of Victoria and Chairman of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, reviewed the case to determine the cause of death and concluded that “There seems little doubt it was digitalis.”[69]Phillips supported his conclusion by pointing out that the organs were engorged, consistent with digitalis, the lack of evidence of natural disease and “the absence of anything seen macroscopically which could account for the death”.[69] Three months prior to the death of the man, on 16 August 1948, an overdose of digitalis was reported as the cause of death for United States Assistant Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White.[70] He had been accused of Soviet espionage under Operation Venona.[71]

Former South Australian Chief Superintendent Len Brown, who worked on the case in the 1940s, stated that he believed that the man was from a country in the Warsaw Pact, which led to the police’s inability to confirm the man’s identity.[72]

The case is still considered “open” at the South Australian Major Crime Task Force.[72] The South Australian Police Historical Society holds the bust, which contains strands of the man’s hair.[5][72] Any further attempts to identify the body have been hampered by the embalming formaldehyde having destroyed much of the man’s DNA.[72] Other key evidence no longer exists, such as the brown suitcase, which was destroyed in 1986. In addition, witness statements have disappeared from the police file over the years.[5]

Mangnoson case

On 6 June 1949, the body of two-year-old Clive Mangnoson was found in a sack in the Largs Bay sand hills, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) down the coast from Somerton.[73] Lying next to him was his unconscious father, Keith Waldemar Mangnoson.[74] The father was taken to a hospital in a very weak condition, suffering from exposure;[73] following a medical examination, he was transferred to a mental hospital.[75]

The Mangnosons had been missing for four days. The police believed that Clive had been dead for twenty-four hours when his body was found.[76] The two were found by Neil McRae[77] of Largs Bay, who claimed he had seen the location of the two in a dream the night before.[78]

The coroner could not determine the young Mangnoson’s cause of death, although it was not believed to be natural causes.[16] The contents of the boy’s stomach were sent to a government analyst for further examination.[73]

Following the death, the boy’s mother, Roma Mangnoson, reported having been threatened by a masked man, who, while driving a battered cream car, almost ran her down outside her home in Cheapside Street, Largs North.[16]Mrs Mangnoson stated that “the car stopped and a man with a khaki handkerchief over his face told her to ‘keep away from the police or else.'” Additionally a similar looking man had been recently seen lurking around the house.[16]Mrs. Mangnoson believed that this situation was related to her husband’s attempt to identify the Somerton Man, believing him to be Carl Thompsen, who had worked with him in Renmark in 1939.[16]

J. M. Gower, secretary of the Largs North Progress Association received anonymous phone calls threatening that Mrs. Mangnoson would meet with an accident if he interfered while A. H. Curtis, the acting mayor of Port Adelaide received three anonymous phone calls threatening “an accident” if he “stuck his nose into the Mangnoson affair.” Police suspect the calls may be a hoax and the caller may be the same person who also terrorised a woman in a nearby suburb who had recently lost her husband in tragic circumstances.[16]

Soon after being interviewed by police over her harassment, Mrs. Mangnoson collapsed and required medical treatment.[79]

Marshall case

In June 1945, three years before the death of the Somerton Man, a 34-year-old Singaporean man named Joseph (George) Saul Haim Marshall was found dead in Ashton Park, Mosman, Sydney, with an open copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam on his chest.[80] His death is believed to be a suicide by poisoning. Marshall’s copy of the Rubaiyat was recorded as a seventh edition published in London by Methuen. In 2010 an investigation found that Methuen had published only five editions; the discrepancy has never been explained and has been linked to the inability to locate a copy of the Whitcombe and Tombs edition.[3]

Jestyn gave Alfred Boxall a copy of the Rubaiyat in Clifton Gardens two months after Marshall’s death. Clifton Gardens is adjacent to Ashton Park. Joseph Marshall was the brother of the famous barrister and Chief Minister of Singapore David Saul Marshall. An inquest was held for Joseph Marshall on 15 August 1945; Gwenneth Dorothy Graham testified at the inquest and was found dead 13 days later face down, naked, in a bath with her wrists slit.[81][82]

Timeline

Real names replace pseudonyms due to their disclosure in 2013.[83]

- 1906 April: Alfred Boxall born in London, England.

- 1912 October: Prosper Thomson, Jestyn’s future husband, is born in central Queensland.[84]

- 1921: Jessica “Powell” (Jestyn) is born in Marrickville, New South Wales.[85]

- 1936: Prosper Thomson moves from Blacktown in Sydney to Melbourne, marries and lives in Mentone, Victoria, a south east Melbourne suburb. [86]

- 1944 June: Alf Boxall’s daughter ‘Lesley’ is born.[87]

- 3 June 1945: “George” Joseph Saul Haim Marshall is found dead from poisoning in Ashton Park, Mosman, Sydney. A copy of the Rubaiyat was found open next to his body. Ashton Park is directly adjacent to Clifton Gardens where Jestyn met Boxall two months later.

- 1945 August: Jestyn gives Alf Boxall an inscribed copy of the Rubaiyat over drinks at the Clifton Gardens Hotel, Sydney prior to his being posted overseas on active service.

- October 1946: Robin Thomson conceived (assuming normal duration pregnancy).

- Late 1946: Jestyn is pregnant and moves to Mentone, Victoria to temporarily live with her parents. [88] (The same Melbourne suburb in which Prosper Thomson had established himself and his then new wife ten years before.)

- Early 1947: Jestyn moves to a suburb of Adelaide and changes her surname to that of her future husband.

- 1947 July: Jestyn’s son Robin is born.[89]

- 15 January 1948: Alf Boxall arrives back in Sydney from his last active duty and is discharged from the army in April 1948. [90]

- July 1948: “Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley Street, Glenelg” appears in Adelaide Local Court as defendant in a car sale dispute, dating from November 1947, establishing Prosper Thomson as active in Adelaide from 1947. [91]

- 30 November 1948. 8:30 a.m. to 10:50 a.m.: The Somerton Man is presumed to have arrived in Adelaide by train. He buys a ticket for the 10:50 a.m. train to Henley Beach but did not use it. This ticket was the first sold of only three issued between 6:15 a.m. and 2 p.m. by this particular ticket clerk for the Henley Beach train.

- Between 11:00 a.m. and 12 noon: Checks a brown suitcase into the train station cloak room.

- after 11:15 a.m.: Buys a 7d bus ticket on a bus that departed at 11:15 a.m. from the south side of North Tce (in front of the Strathmore Hotel) opposite the railway station. He may have boarded at a later time elsewhere in the city as his ticket was the sixth of nine sold between the railway station and South Tce however, he only had a 15-minute window from the earliest time he could have checked his suitcase (the luggage room was around 60 metres from the bus stop). It is not known which stop he alighted at. The bus terminated at Somerton at 11:44am however, enquiries indicated that he “must have” alighted at Glenelg, a short distance from the St. Leonard’s hotel.[92] This stop is less than 1 kilometre (3,300 ft) north of the Moseley St address of Jestyn, which was itself 400 m from where the body was found.

- 7 p.m.–8 p.m.: Various witness sightings.

- 10 p.m.–11 p.m.: Estimated time he had eaten the pasty based on time of death.

- 1 December, 2 a.m.: Estimated time of death. The time was estimated by a “quick opinion” on the state of rigor mortis while the ambulance was in transit. As a suspected suicide, no attempt to determine the correct time was made. As poisons affect the progression of rigor, 2 a.m. is probably inaccurate.

- 6:30 a.m.: Found dead by John Lyons and two men with a horse.

- 14 January 1949: Adelaide Railway Station finds the brown suitcase belonging to the man.

- 6 June: The corpse of Clive Mangnoson is found 20 km away from Somerton by Neil McRae.

- 6–14 June: The piece of paper bearing the inscription “Tamám Shud” is found in a concealed fob pocket.

- 17 and 21 June: Coroner’s inquest[93]

- 22 July: A man hands in the copy of the Rubaiyat he had found on 30 November containing the secret code. Police later match the “Tamám Shud” paper to the book.

- 26 July: An unlisted phone number discovered in the book is traced to a woman living in Glenelg. Shown the plaster cast by Paul Lawson, “Jestyn” could not confirm or exclude that the man was Alf Boxall. Lawson’s diary entry for that day uses the name “Mrs Thompson” and stated that she had a “nice figure” and is “very acceptable” (referring to the level of beauty) which allows the possibility of an affair with the Somerton man. She was 27 years old in 1948. In a later interview Lawson described her behaviour as being very odd that day. Also she appeared as if she was about to faint.[94] The following day Sydney detectives interview Alf Boxall. “Jestyn” requests that her real name be withheld because she didn’t want her husband to know she knew Alf Boxall. Although she was in fact not married at this time, the name she gave police was Jessica Thomson with her real name not being discovered until 2002.[59]

- Early 1950: Prosper Thomson’s divorce is finalised.

- 1950 May: Jestyn marries Prosper Thomson.

- 1950s: The Rubaiyat is lost.

- 14 March 1958: The coroner’s inquest is continued. Jestyn and Alf Boxall are not mentioned. No new findings are recorded and the inquest is ended with an adjournment sine die.[95]

- 1986: The Somerton Man’s brown suitcase and contents are destroyed as “no longer required”.

- 1994: The Chief Justice of Victoria, John Harber Phillips, studies the evidence and concludes that poisoning was due to digitalis.

- 1995: Jestyn’s husband Prosper dies.

- 17 August 1995: Alf Boxall dies.

- 2007 May: Jestyn dies.

- 2009 March: Jestyn’s son Robin dies.

Current investigation

In March 2009 a University of Adelaide team led by Professor Derek Abbott began an attempt to solve the case through cracking the code and proposing to exhume the body to test for DNA.[96]

Abbott’s investigations have led to questions concerning the assumptions police had made on the case. Police had believed that the Kensitas brand cigarettes in the Army Club packet were due to the common practice at the time of buying cheap cigarettes and putting them in a packet belonging to a more expensive brand (Australia was still under wartime rationing). However, a check of government gazettes of the day indicated that Kensitas were actually the expensive brand, which opens the possibility (never investigated) that the source of the poison may have been in the cigarettes that were possibly substituted for the victim’s own without his knowledge. Abbott also tracked down the Barbour waxed cotton of the period and found packaging variations. This may provide clues to the country where it was purchased.[61]

Decryption of the “code” has been started from scratch. It has been determined that the letter frequency is considerably different from letters written down randomly; the frequency is to be further tested to determine if the alcohol level of the writer could alter random distribution. The format of the code also appears to follow the quatrain format of the Rubaiyat, supporting the theory that the code is a one-time pad encryption algorithm.[dubious ] To this end, copies of the Rubaiyat, as well as the Talmud and Bible, are being compared to the code using computers in order to get a statistical base for letter frequencies. However, the code’s short length may require the exact edition of the book used. With the original copy lost in the 1960s, researchers have been looking for a FitzGerald edition without success.[61]

The media has suggested that Jestyn’s son, who was 16-months old in 1948 and died in 2009, may have been a love child of either Alf Boxall or the Somerton Man and passed off as her husband’s. DNA testing would confirm or eliminate this speculation.[96] Abbott believes an exhumation and an autosomal DNA test could link the Somerton man to a shortlist of surnames which, along with existing clues to the man’s identity, would be the “final piece of the puzzle”. However, in October 2011, Attorney General John Rau refused permission to exhume the body stating: “There needs to be public interest reasons that go well beyond public curiosity or broad scientific interest.”

Feltus said he was still contacted by people in Europe who believed the man was a missing relative but did not believe an exhumation and finding the man’s family grouping would provide answers to relatives, as “during that period so many war criminals changed their names and came to different countries.”[99]

As one journalist wrote in 1949, alluding to the line in The Rubaiyat, “the Somerton Man seems to have made certain that the glass would be empty, save for speculation.”[1]

In July 2013 Abbott released an artistic impression he commissioned of the Somerton man, believing this might finally lead to an identification. “All this time we’ve been publishing the autopsy photo, and it’s actually hard to tell what something looks like from that,” Prof Abbott said.[100]

H. C. Reynolds

In 2011, an Adelaide woman contacted Maciej Henneberg about an identification card of an H. C. Reynolds that she had found in her father’s possessions. The card, a document issued in the United States to foreign seamen during WWI, was given to biological anthropologist Maciej Henneberg in October 2011 for comparison of the ID photograph to that of the Somerton man. While Henneberg found anatomical similarities in features such as the nose, lips and eyes, he believed they were not as reliable as the close similarity of the ear. The ear shapes shared by both men were a “very good” match, although Henneberg also found what he called a “unique identifier;” a mole on the cheek that was the same shape and in the same position in both photographs.[101]

“Together with the similarity of the ear characteristics, this mole, in a forensic case, would allow me to make a rare statement positively identifying the Somerton man.”

The ID card, numbered 58757, was issued in the United States on 28 February 1918 to H.C. Reynolds, giving his nationality as “British” and age as 18. Searches conducted by the US National Archives, the UK National Archives and the Australian War MemorialResearch Centre have failed to find any records relating to H.C. Reynolds. The South Australia Police Major Crime Branch, who still have the case listed as open, will investigate the new information.[101]

Developments

In 2013, relatives of Jessica and Prosper Thomson gave interviews to the television current affairs program 60 Minutes, which was aired on 24 November. On the program, Kate Thomson, the daughter of Jessica and Prosper Thomson, claimed that her mother had told her that she (Jessica): had lied to police; did know the identity of the “Somerton Man” and; his identity was also “known to a level higher than the police force”.[102] Kate Thomson also suggested that her mother and the “Somerton Man” may both have been spies, noting that Jessica Thomson was interested in communism and could speak Russian, although she would not disclose to her daughter where she had learned it, or why.[102]

Robin Thomson’s widow, Roma Egan and their daughter, Rachel Egan, also appeared on 60 Minutes suggesting that the “Somerton Man” was Robin Thomson’s father and, therefore, Rachel’s grandfather. The Egans reported lodging a new application with the Attorney-General of South Australia, John Rau, to have the body exhumed and DNA tested.[102]

Derek Abbott also subsequently wrote to Rau in support of the Egans, saying that exhumation for DNA testing would be consistent with federal government policy of identifying soldiers in war graves, to bring closure to their families. Kate Thomson opposes the exhumation as being disrespectful to her brother.[83][102]

Cultural references

- Tamam Shud was the name of a progressive rock and psychedelic surf band formed in Sydney, in 1967.

- Episode 3 of the second series of The Doctor Blake Mysteries, A Foreign Field draws heavily on the case. The story included a mysterious victim found slumped up dead in a public place, a suitcase of clothes found in a railway station locker with all labels removed, a page of a poem used with a secret code and even the victim’s last meal being a pasty.

Notes

- While the words that end The Rubaiyat are “Tamam Shud” (تمام شد), it has often been referred to as “Taman Shud” in the media, presumably because of a spelling error that persisted. In Persian, تمام tamám is a noun that means “the end” and شد shud is an auxiliary verb indicating past tense, so tamam shud means “ended” or “finished”.

- The taxidermist who made the plaster cast testified at the inquest that he thought the Somerton man had been in the habit of wearing some type of high-heeled, pointed shoes, as the calf and toe characteristics were predominantly found in women because of their shoe styles. Police had earlier investigated if the man had been a stockman in Queensland based on the same physical traits, perhaps associated with cowboy/stockman style boots. See page 7 of the Cleland, 1949 Inquest

- With wartime rationing still enforced, clothing was difficult to acquire at that time. Although it was a very common practice to use name tags, it was also common when buying second hand clothing to remove the tags of the previous owner/s.

- Although named the City Baths, the centre was not a public bathing facility but a public swimming pool. The railway station bathing facilities were adjacent to the station cloak room, which itself was adjacent to the station’s southern exit onto North Terrace. The City Baths on King William St. were accessed from the stations northern exit via a lane way.

- It is now known that the two drugs were number 1:digitalis and number 2:strophanthin .

- This particular edition of the Rubaiyat has a different translation compared to other FitzGerald translations.

- The media usually refer to the wo

All or part of the article above was taken from the Wikipedia article Taman Shud Case, licensed under CC-BY-SA.